Recovered from jet lag, we met our guide and the other members of our touring group in the hotel lobby Friday morning. We were also greeted by our travel agent, Severa, who has been extremely helpful in making all our travel arrangements. I was not surprised to learn she is one of Advantour’s most senior managers.

It was immediately apparent that our guide, Ahror (pronounced “Ahk-roar”), was also one of Advantour’s best, a very professional contracted guide. A native of Bukhara, he exhibited obvious pride of place and soon proved to be affable, informed, considerate and resourceful.

Our traveling companions for this “-Stans” part of the trip are all younger than us: a Canadian couple (she an expat American); two Australians (university girlfriends); and three Hong Kongers (a couple and their friend, former financial coworkers from the Philippines) – all seasoned travelers and, as it turned out, all friendly, fascinating people.

Shuttled around town, our first stop was the monument dedicated to the men and women who rebuilt Tashkent following the terrible 1966 earthquake that devastated the city, destroying most of the buildings and leaving nearly 300,000 homeless. The quake was so destructive because its epicenter was directly beneath the city center, just two miles below the surface.

Buildings here in those days, mostly 1- or 2-story mud-brick structures lacking steel reinforcement, simply crumbled. Only a few significant structures survived.

The most historical of the surviving buildings are located in what is now known as the Khazrati-Imam Complex, shown below. Most of these structures date back to the 1500s, having been renovated and restored in the 2000s (you can see that some work is still ongoing).

The Khazrati-Imam Complex includes several mosques and madrassas (one is still functioning), and the mausoleum of a famous Tashkent muslim cleric, spiritual leader and poet, Abu Bekr Al-Kaffal Al-Kabir Ash-Shashi, known colloquially as “Kaffal,” the locksmith.

The interiors of these buildings are shown below. One of the madrassas houses the Uthman Koran, believed to be the oldest extant Koran in the world, transcribed in the 8th century following the days of the Prophet. Unfortunately, photography of the book was prohibited.

Given that the “-Stans” are all predominantly Sunni Muslim, the buildings of the Khazrati-Imam Complex are representative of what we expect to see over the next few days.

As I mentioned in a previous post, my interest in Central Asia was peaked by the story of Marco Polo and the Silk Road. But I always assumed this region to be culturally Asian, based on the fact that it was the Mongol founder of the Yuan dynasty in China, Kublai Khan (1215-1294), that the Polos went to trade with. Kublai Khan was the grandson of the infamous 13th century warrior and uniter of nearly all of Asia, Genghis Khan (1162-1227).

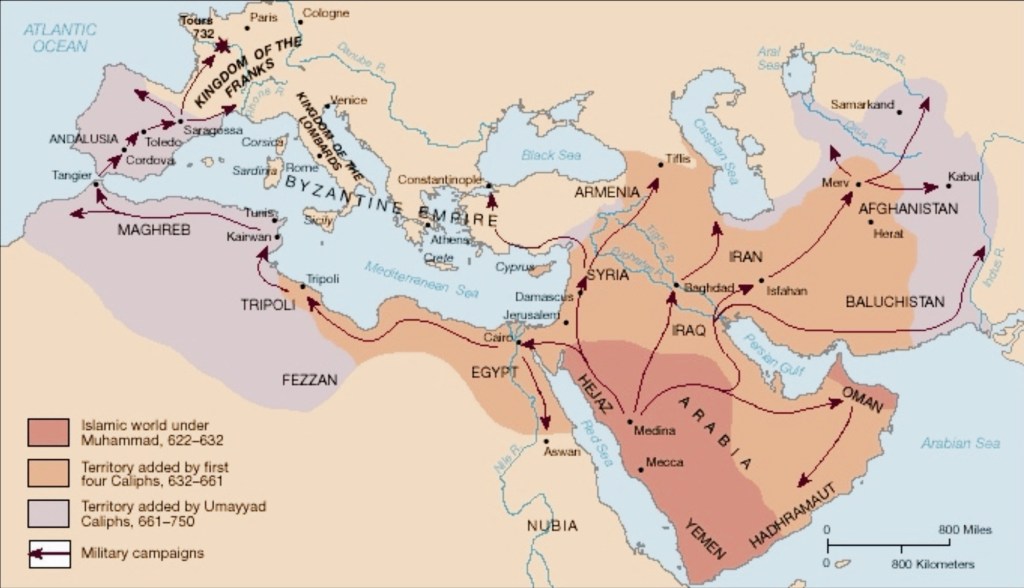

But long before then, Central Asia had been conquered by the Persians (Achaemenid Empire, 550 BC to 330 BC), then the Greeks (Alexander the Great, 327 BC), then the Persians again (Sassanid Empire, 224 AD to 651 AD), and finally by Arab marauders, beginning around 651 AD, who brought Islam with them.

Arab expansion halted just northeast of Tashkent when the Arab Abbasid Caliphate clashed with the Chinese Tang Dynasty at the Battle of Talas in 751 AD. By 960 AD, nearly all the tribes of Central Asia had been conquered and converted to Islam. It has remained so ever since.

Our next stop after the Khazrati-Imam Complex was the Chorsu Bazaar, a domed marketplace housing butchers selling, among other things, horse meat,…

… and numerous vendors featuring spices, nuts, dried fruits and fresh vegetables:

There was a special area for the bakers, who still use the traditional domed-oven, slapping the dough against the oven’s sides for baking.

The smell of fresh bread, non, as it is known here, brought out our appetite, so we were whisked off to Besh Qozon, famous for its palov (pronounced “plov”), the national dish. It’s a mixture of long-grain rice, tender chunks of lamb (or beef), carrots and onions.

Although this restaurant undoubtedly draws hosts of tourists, it also appeared to be a local favorite. Entering, we watched the palov being prepared, the feature event being the final mix in the giant kazan, a huge wok-like frying pan. For anyone interested in trying it, here’s an authentic recipe.

After lunch, we made a brief stop at the State Museum of Applied Arts to see exhibits of traditional crafts, such as musical instruments, tapestries and head coverings:

We then went underground to take a ride on the mostly-subterranean Tashkent Metro. We descended to the Cosmonaut station where we caught a train to another station and switched lines (Ahror is pointing out where we started, below):

Construction of the Tashkent Metro began in 1968, two years after the devastating 1966 earthquake. The first line (the red one) opened in 1977, the 60th Anniversary of the Soviet Union. Several more lines and extensions have been added since then, most recently in 2023. There are now 50 operating stations, a few of which are above ground.

Our final stop for the day was the Amir Timur Square which hosts a monument dedicated to the Uzbek hero, Timur (1320s-1405).

I’ll have more to say about Timur in my next post, but for know, let’s just note that Timur, known in the West as Tamerlane, was the founder of the Turco-Mongol Timurid Empire that extended throughout Central Asia, the Caucuses and beyond from 1370 to 1507.

To the left behind Timur’s monument, in the photo above, is the Soviet-era Hotel Uzbekistan. Timur rides his horse atop the location where a statute of Karl Marx once stood. Another empire defenestrated.