We are ready now to ease our way back into the past.

Our tour itinerary will take us first to Samarkand, one of the oldest, continuously inhabited cities of Central Asia. After a brief detour into neighboring Tajikistan for a trek up into the Fann Mountains to visit the Seven Lakes, we will pick up the Silk Road at Ancient Penjikent and follow it back to Samarkand and on to Bukhara.

Then, on to the eccentric capital of Turkmenistan, Ashgabat. From there we’ll drive across the Karakum Desert, ending our time in Central Asia back in Uzbekistan at Khiva.

We were up early Saturday to catch the high speed train, Afrosiyob, from Tashkent to Samarkand.

Upon arrival in Samarkand, we immediately transferred to a Sprinter van and headed for the Gūr-e Āmir Mausoleum (Persian for “Tomb of the King”), the final resting place of Tamerlane (1320s-1405). We’ll call it Gur Emir, the Anglicized version.

Here’s a view of the restored principal structures:

Tamerlane ordered construction of Gur Emir to be the burial place of his favored grandson and intended heir to the throne, Muhammed Sultan, who died of wounds sustained in battle against the Ottomans in 1403. And Muhammed Sultan is indeed entombed here. But so is Tamerlane himself, although that was not his intent.

Tamerlane had directed that his own remains were to be interred at the place of his place of birth, Shahrisabz, 50 miles to the north. But at the time of his death in the winter of 1405, the mountain pass to that place was impassable, so his body was laid to rest at Gur Emir alongside his grandson.

Entrance to the mausoleum and its attached chapel is gained through this archway…

… which features a stalactite motif above.

Dale was taken by the beautiful tile work on the facade of the archway.

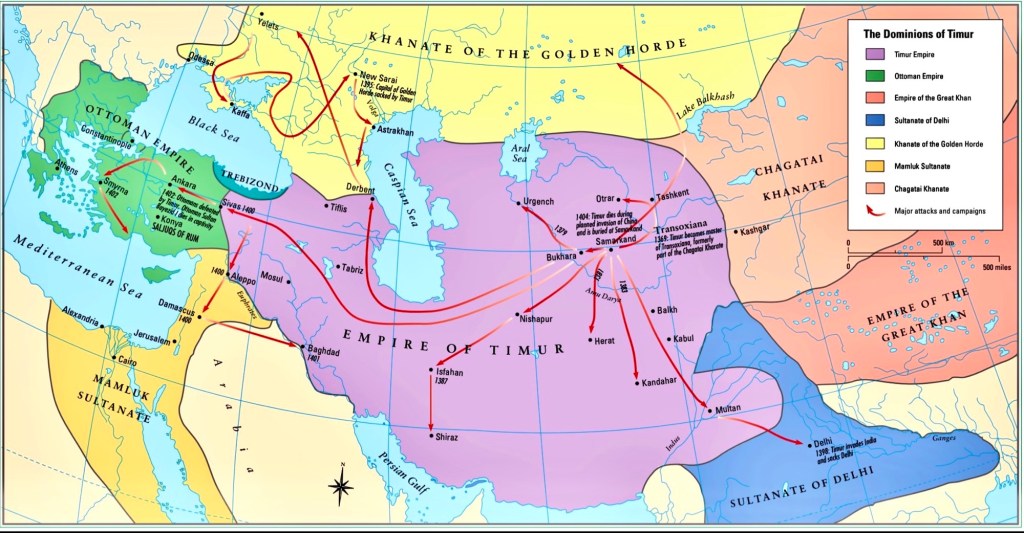

As I mentioned in my last post, Tamerlane, known in Uzbekistan as Timur, was founder of an empire that encompassed all of Central Asia and the Caucuses, as well as other parts of Asia, Eurasia, India and the Middle East.

The westernized “Tamerlane” comes from Timur the Lame. As a young mongol warrior, Timur was wounded in battle leaving him crippled in one leg and short of a few fingers.

He was known as a fierce fighter and tactical genius. So much so that he rose through the ranks to ultimately take over the Chagatai Khanate, the domain of one of Ghengis Khan’s sons that encompassed Central Asia, by 1370 AD.

With the Chagatai as his power base, he spent the next 35 years campaigning out of Samarkand, subduing all the surrounding kingdoms. Those who submitted to his demands were spared, but any who resisted were brutally massacred and beheaded – men, women and children – their skulls stacked into towers as a warning to others.

It has been asserted that Tamerlane was responsible for 17 million deaths, the outrageous cost of empire. As terrible as our modern wars have been, horrific conflict is not new to mankind.

We continued to the chapel and mausoleum through the main archway.

The mausoleum is to the right of the dome and accessed from inside the chapel.

This is a view of the dome from inside:

Ultimately, Gur Emir became the family crypt of the Timurid Dynasty. Besides Timur and Muhammed Sultan, two of Timur’s sons, as well as another famous grandson, Ulugh Beg, are also interred here.

Timur’s burial place is marked by the dark green jade block in the center of the photo below (left). The walls of the mausoleum are tiled in green onyx which is translucent, as Ahror exhibited (right).

Leaving the mausoleum, we wandered around back where we could see the original structure adjacent to a restored section.

Tamerlane’s empire endured until 1507 when Central Asia broke apart into several khanates, similar to the city-states of feudal Europe.

The Timurid Dynasty marked the end of a conflict that afflicted Central Asia since time immemorial: the tug of war between the raiding nomads of the steppe, and the sedentary farmers and city dwellers of the fertile valleys and lands between the rivers.

For millennia, the nomads had raided, invaded, pillaged and conquered, only to fade back into the desert and grasslands of the steppe where they were nearly invincible, moving with their herds and yurts where the wind blew them.

Now, like the victims of their brutality, they are dust in the wind.