The Greater Caucasus Mountains, stretching from the Black Sea on the west to the Caspian on the east, constitute a formidable barrier for transit between Russia and Georgia. As consequence, the ridgeline coincides with the political boundary between these two nations, also separating, geologically, the continents of Europe and Asia. Mt. Erebus is the highest Caucasian peak at 18,510 feet, taller than the highest mountain of the Alps by 2,730 feet.

There are roads running along the coastlines at the edges of the mountains: one along the Black Sea from Sochi, Russia, to Poti, Georgia; the other on the Caspian between Grozny, Russia, to Baku, Azerbaijan. But there is only one open, passable road between Georgia and Russia through the interior of the Greater Caucasus Mountains, and that is the Georgian Military Road.

The track of the Georgian Military Road dates back to Roman times, existing only as a rough horse trail when Russian troops first used it to access the lands to the south in 1769. To put that into perspective, let me pick up where I left off regarding the history of Georgia in my last post.

Recall that by the 1400s the Christian Kingdom of Georgia, formerly Iberia, had survived the Arab (700s AD) and Mongol invasions (1222 AD). It had also survived an invasion by Tamerlane in the 1300s AD. But now it was surrounded by Muslims realms, including Persia to its south. Georgia’s only Christian allies were the Romanic Byzantines to the west and, potentially, the Russian Empire just then forming to the north.

In 1453 AD, Byzantium was defeated by the Ottoman Turks, leaving Georgia isolated in an Islamic world south of the Greater Caucasus. But the Ottomans were Sunni Muslims and the Persians were Shiite. That sectarian difference soon led to an Ottoman-Persian war that was to last many years, an on-again-off-again conflict that overflowed onto Georgian territory. Amidst the turmoil, he Kingdom of Georgia fell apart.

The conflict weakened the Ottoman and Persian Empires and the Russians took advantage of their attritted state, slowly expanding to the south. Realizing that Persia was the weaker of the two, Russian tsar Peter the Great launched a “Persian Campaign” to take Baku in 1722.

The result was a stalemate between the Ottomans, Russians and Persians which by 1735 they resolved through treaties dividing the lands south of the Greater Caucasus Mountains among them. But the treaties were soon broken and in 1768 a Russian-Ottoman war erupted, with the Russians ultimately victorious.

In the vacuum created by the devastation of war, a new Georgian king arose, Irakli II (1762-1798), once again uniting the Georgian people. But King Irakli II understood the need for Russian protection against further threat from the Persians and Ottomans, so he proposed an alliance with Russia, set forth in the 1783 Treaty of Georgievsk that made the Kingdom of Georgia a Russian protectorate.

The Russians sent 800 troops to improve what came to be known as the Georgian Military Road over the Greater Caucasus and by October 1783, the general in charge of the project was able to drive his horse-drawn carriage on the road all the way to Tbilisi.

The map below depicts the route of the Georgian Military Road today in red. The blue line is the international boundary between Russia and Georgia. All of the sites that I described in my last post (Tbilisi, Uplistikhe, Jvari Monastery, Mtskheta, Ananuri, Gudauri and the Gergeti Church near the international border, marked by a red dot) can be found on this map.

[Note: The Transcaucasian Highway border crossing between South Ossetia and Georgia, in yellow on the map, above, has been closed since 2008 as a result of the Russo-Georgia War that I will discuss below.]

As we drove north on the Georgian Military Road toward Stepantsminda and the Gergeti Church, it began to rain.

The border crossing between Russia and Georgia was closed in 2006, but reopened in 2013, as a result of Armenian demands. As you can see from the volume of trucks heading south for Armenia from Russia, the road is once again an important transportion artery. Trade has also resumed between Russia and Georgia, to the dismay of the European Union and NATO.

About 25 miles south of the border is the Russia–Georgia Friendship Monument, built by the U.S.S.R. in 1983 to celebrate the then-friendship between the Soviet Socialist Republics of Russia and Georgia and the bicentennial of the Treaty of Georgievsk (1783), discussed above.

The rain had not let up and the trek up to the monument from the parking area was rather muddy.

The mosaic covering the Friendship Monument is said to depict scenes from Russian and Georgian history, but their abstract meaning was lost on me.

The view of the surrounding mountains was fantastic.

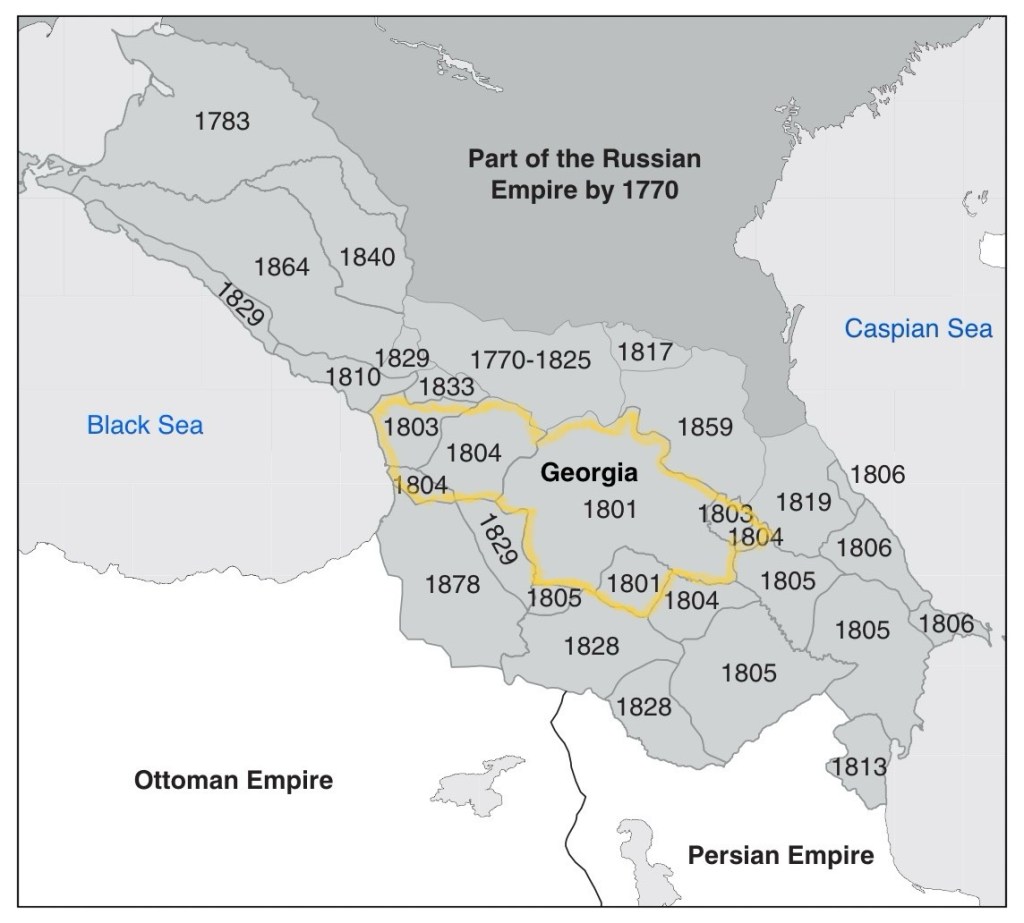

After the Treaty of Georgievsk in 1783, the Russian Empire continued its expansion into the lands of the southern Caucasus and by 1830, the entire region that now includes Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia was incorporated into the Russian Empire.

Skipping ahead in time, World War I (1914-1918 AD) was the war that ended empires. The German, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires were all destroyed and dismantled by that “War to End All Wars,” as it was then called.

From 1918 through 1920, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia all briefly became independent nations. They then joined together to create a single Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic (T.S.F.S.R.) that merged with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the U.S.S.R., in 1922.

In 1936, the T.S.F.S.R. split into three new sovereign republics, the Georgian, Azerbaijan and Armenian Soviet Socialist Republics (S.S.R.), as shown on the right in the map below. The intent was to align the borders of each S.S.R. with the ethnicity of the populace. Where that could not be accomplished, Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republics (A.S.S.R.) or Autonomous Oblasts (A.O.) were created to do the same thing on a smaller scale.

The distinction between these entities is that: an S.S.R. is like sovereign state; an A.S.S.R. is an administrative unit within an S.S.R., like a county; and an A.O. is subordinate to both, like a township or community.

As we drove south on the Georgia Military Road, we passed the South Ossetia A.O. (Autonomous Oblast) to the right:

The South Ossetia O.A., as well as the Abkhazia A.S.S.R. to its west, were both involved in separatist movements that began in the late-1980s as the U.S.S.R. began to unwind.

With the encouragement and support of Russia, by 2008 these movements had escalated to all-out war when Georgia invaded South Ossetia to put down a separatist revolt there. The full dispute, which came to be known as the Russo-Georgian War, is far too complex for me to discuss in depth here.

Suffice to say that from the Russian perspective, the cause of the war was the commitment by NATO at its 2008 Bucharest Summit to include Georgia within its membership, much like what took place in 2022 with regard to Ukraine.

From the Georgian perspective, the war was simply an opportunistic, expansionary invasion by Russia into Georgian territory, with the separatist movements merely being a ruse to do so.

Villages were shelled and cities bombed. Tanks rolled in. The fighting lasted 5 days, hundreds of soldiers and citizens were killed, and around 200,000 residents were displaced, including our bus driver, a former South Ossetian.

The war concluded with: the military occupation of the two regions by Russia; the removal of ethnic Georgians from the occupied lands; and severance of diplomatic relations between Georgia and Russia, all of which continue to this day.

A great irony of the Russo-Georgian War is that Russia bombed and occupied the city of Gori, the birthplace of Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, known to the world as Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1952.

We visited the Joseph Stalin Museum in Gori as we finished our time in Georgia. That’s it on the left (top photo below) with a statue of Stalin on the right facing it. The frames in the middle show the shrine built around the house that Stalin grew up in. The bottom photo was taken from in front of the shrine, looking at the park that was created by displacing an entire neighborhood for its development. The museum opened in 1957.

In the aftermath of the Russo-Georgian War, Georgians contemplated renaming the museum the “Museum of Russian Aggression.”

Wikipedia (which is unreliable regarding anything political) claims that “the overall impression [of the museum] is that of a shrine to a secular saint.” And tour guides smirk at the exhibits.

But, while I am no fan of Stalin or the Soviet Union, I did find the museum’s exhibits to be informative. Clockwise from the statue of the dictator are: the bullet-proof train car Stalin used to go to the Yalta and Tehran conferences; the desk and furnishings from his executive office while General Secretary; and early photos, those on the bottom row being Stalin as a boy, flanked by his mother and father.

And now, we’re headed for our last stop, Armenia.