We enjoy being in the countryside while traveling, seeing every day life through the eyes of the common man. So, after spending a few days in the big city, we were ready for something less hectic: the train from Bangkok’s Thonburi Station to Kanchanaburi along the route of the famous Burma Railway.

It’s only a distance of 75 miles between Thonburi and Kanchanaburi stations, but being a local train, we made several stops along the way. It was fun, if not exactly luxurious, with fans instead of air conditioning, upright benches instead of padded seats, and, hawkers boarding at each stop selling quail eggs and tropical fruit. The trip took about 2.5 hours.

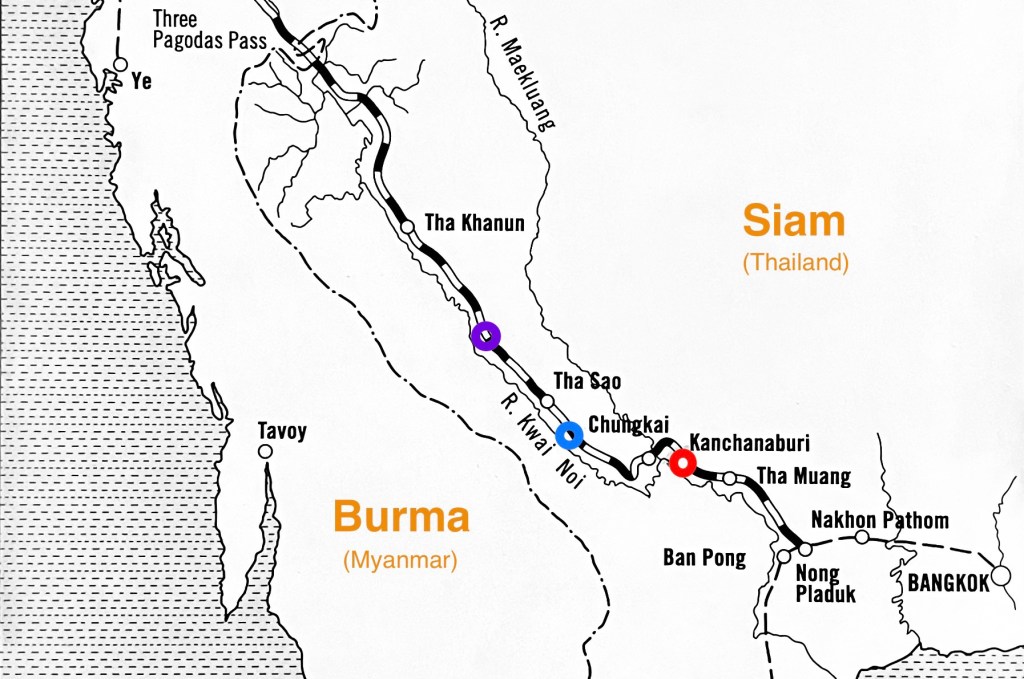

The track currently ends at Nam Tok Station, another 40 miles west of Kanchanaburi, but when the railway was built during World War II, it ran all the way to Burma (modern-day Myanmar), a distance of 258 miles from its junction with the then-existing track running southwest out of Bangkok.

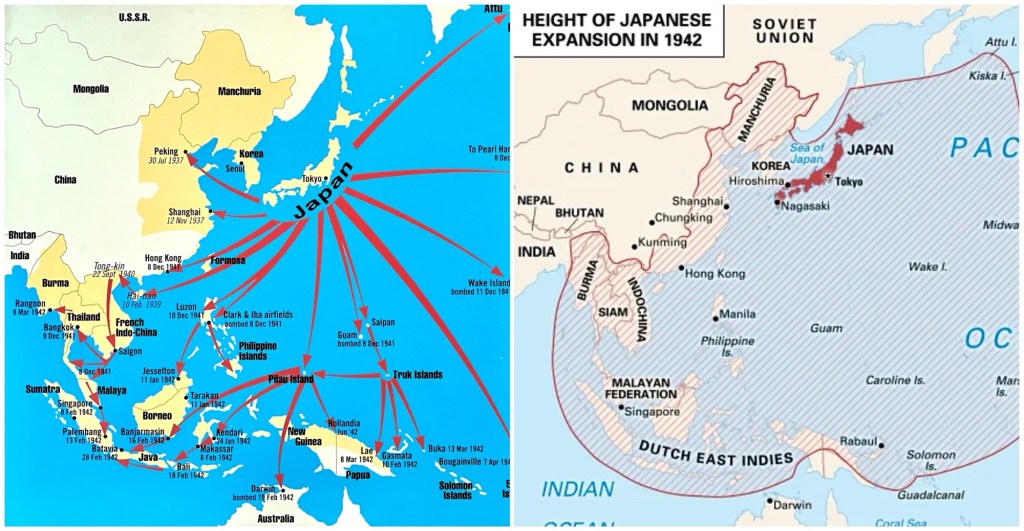

Thailand, which officially changed its name from Siam in 1939, was a neutral country at the beginning of World War II when Japan invaded on December 8, 1941, the same day the Japanese launched a surprise attack on the U.S.A. at Pearl Harbor (where, being east of the International Dateline, it was still December 7th).

Thailand quickly surrendered and entered into an alliance with Japan and the Axis Powers, making Thailand a base from which the Japanese could conduct military operations throughout Southeast Asia. As Japan’s ally, Thailand declared war on the United States and the United Kingdom on January 25, 1942.

By the end of March 1942, Japan was in control of the entire Pacific Theater west of Hawaii. At its outer limits, Japan had bombed Darwin, Australia, driven the British out of Burma, and sets its sights on India.

In Kanabanchuri, we stayed at the Good Times Resort on the Khwae Yai (the “Big River Kwai”) which merges just downstream with the Khwai Noi (the “Little River Kwai”).

Our room had a nice deck extending out over the water and the room itself was relatively comfortable, once I wrestled the giant bear cub out of his chair.

In anticipation of traveling further west along the railroad to visit its historical WWII sites, we hailed a moped tuk-tuk with a sidecar to take us into town to the Thailand-Burma Railway Centre and war museum, located across the street from the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery. There are 7,000 Allied soldiers buried there, mostly Australian, British and Dutch prisoners-of-war (POWs), forced into slave labor by the Japanese to build the rail.

The Japanese decided to build the Burma Railway, known among the POWs as the “Death Railway,” in order to supply their troops in Burma after the May and June 1942 naval battles of the Coral Sea and Midway. The result of these Allied victories was the closure of the sea-lanes between Japan and Burma, so an overland route had to be substituted.

By this time, the Allied strongholds in the Pacific at Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) had fallen, and Japan held about 140,000 Allied POWs. From this pool of captive labor, the Japanese sent over 60,000 men to work the Death Railway: 30,000 Brits, 13,000 Aussies, 18,000 Dutch and 700 Americans. Many more Southeast Asians were conscripted, estimates exceed 200,000, mostly from China, Burma, Java and Malaya.

Construction began in June 1942 and the railway was completed 16 months later in October 1943. Over 13,000 Allied POWs died; civilian conscript deaths may have exceeded 100,000.

On the map, below, the dashed line running from Bangkok south is the railroad that existed prior to WWII; the black-and-white line is the Death Railway. I have highlighted Kanchanaburi in red and the two historical sites we visited in blue and purple, the Bridge on the River Kwai and Hellfire Pass, respectively.

We hired a driver (below, top left) to take us first to the memorial and visitor center at Hellfire Pass, a cut 250 feet long and 80 feet deep hand-hewn through solid rock at Konyu, 45 miles west of Kanchanaburi. Leaving the visitor center, we walked down a few hundred steps to the old railway bed (top right), then hiked it a ways to Hellfire Pass cut (bottom).

Below is a view from the old railroad bed, looking out at the surrounding terrain. It’s hard to fathom how miserable it must have been to work on the rail here with the extreme heat and humidity. And then came the monsoons. Many of the deaths were from dysentary and diarrhea, but cholera and malaria were also killers, as was starvation and simple exhaustion. The railway beyond Nam Tok was dismantled shortly after the war.

From Hellfire Pass, we headed back toward Kanchanaburi, stopping to see the bridge that was the subject of the 1957 Academy Award winning (7, including Best Picture) movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai. The movie is not historically accurate – there was no bridge built across the River Kwai, nor was it filmed here (it was filmed in Sri Lanka). But it does a pretty good job of depicting the lives of the POWs who labored here. At any rate, it was a great movie. We recently rewatched it. Epic.

The movie made famous the Colonel Bogie March, a tune originally composed in 1914. In the movie, it’s whistled by the POWs as they march back into camp, but soldiers during WWII sang it with bawdy lyrics, to-wit, “Hitler has only got one ball.” I know the song well. I played trumpet in elementary school and our one and only concert featured Colonel Bogie. Ta dum, ta da da dum dum da.

Here’s the actual Bridge on the River Kwai:

And here’s the river itself, looking upstream:

There’s a cave in the cliff face next to the track that once served as a camp for the POWs. It’s now a Buddhist temple of sorts.

On our drive back to Kanchanaburi, we were amused by several monkeys dangling from the power lines and rummaging in the vegetation along the road. We were also amused by the railroad crossing gates that are rolled out by hand (bottom left) when trains approach. I doubt that meets OSHA standards.

Our last day in Thailand was spent walking around town with our main destination being the Jim Thompson House Museum. It’s located on one of the many canals that run throughout Bangkok.

The Jim Thompson House is actually a collection of five traditional Thai houses that were relocated and rebuilt in Bangkok beginning in 1958 by Jim Thompson, a former British architect turned Thai silk entrepreneur. Thompson led an interesting life and died a mysterious death in 1967, disappearing while visiting friends in the Malaysian highlands. Here’s his house:

This photo, taken during our walk back to the hotel, is typical of downtown Bangkok. Notice the elephant statuettes on the right.

We’ve enjoyed seeing a small part of Thailand. Now we’re off to Singapore for a few days.