In order to better describe the culture and history of Thailand, I’m going to tell you about our first days in Bangkok in reverse order. On our second full day as tourists, we hired a guide and driver to take us north 50 miles to visit the Ayutthaya Historical Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1991.

Tai-speaking people (which includes the ancestors of modern Thai) originally came to this part of southeast Asia from northern Vietnam by way of southern China and Burma, shortly after the end of the first millennium. At the time of their arrival, the area was already inhabited by the Buddhist Mon people of Burma and the predominately Hindu-influenced Khmer of Cambodia.

The Tai settled along the fertile Chao Phraya, Lop Buri, and Pasak river basins, and by 1350 A.D., they began building significant structures at the confluence of these three rivers, establishing the city-state of Ayutthaya. As the kingdom’s influence expanded, its people became known as the Siamese, and Siam ultimately evolved into modern-day Thailand, so-named in 1939.

With access to the Gulf and South China Sea via the Chao Phraya River, Ayutthaya became one of the great mercantile centers of Asia for the 400 years subsequent to its founding.

During that time, the Siamese adopted Theravada Buddhism as their principal religion, and Brahmanism as their means of government administration, although their king ruled as a divine and absolute monarch. Even today, 95% of the Thai population is Buddhist, although their government is now a constitutional monarchy with a bicameral parliament.

Also during this period, the Siamese opened to European trade, but never became a colony of any European nation.

Until 1767, things were humming along just fine, but that year, Ayutthaya was attacked from the north by the Burmese. After a 14-month siege, the Siamese were forced to abandon Ayutthaya. The Burmese took over the city and destroyed nearly everything, leaving only a handful of structures standing. It is those relics that we came to see.

As a result of the Burmese invasion, the Siamese capital was moved downstream to the west bank of the Chao Phrya River, opposite the village of Bangkok, very near where our hotel is located.

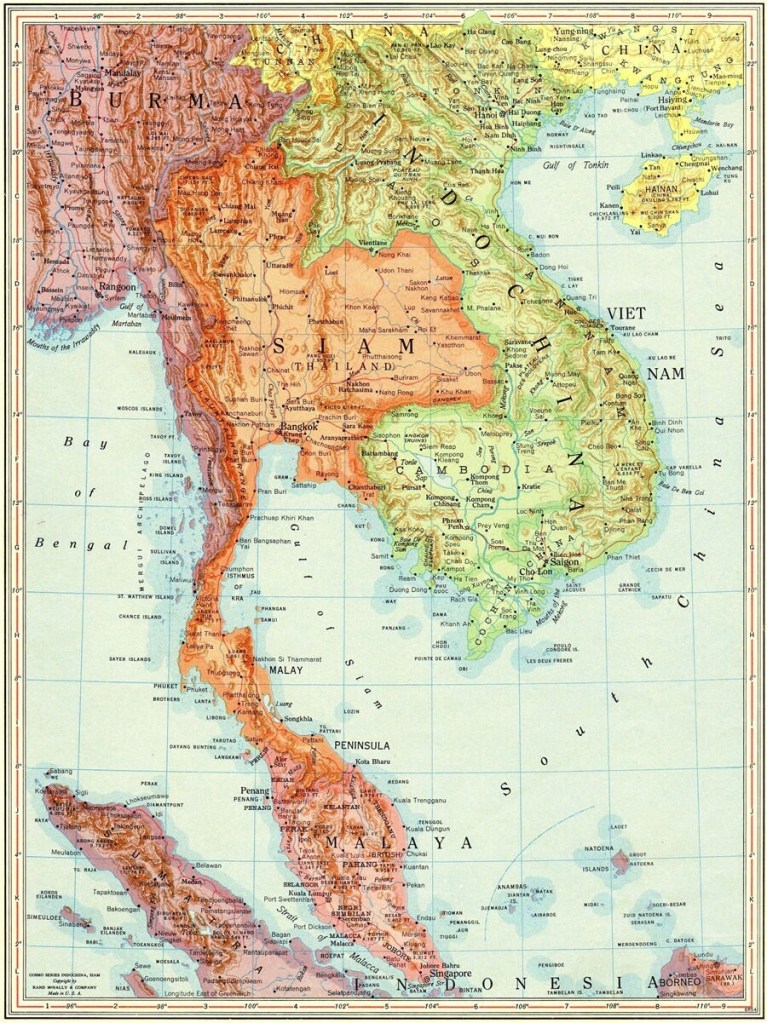

Here’s a map of southeast Asia during the early days of Siam and Burma:

At its peak, Ayutthaya was an agglomeration of wats and palaces.

What is a wat, you ask?

A Theravada Buddhist wat is a temple or monastery complex serving as a religious, cultural and community center where people worship, ceremonies are held, and monks might live. It’s a place for meditation and prayer.

The word wat comes from the Sanskrit word vāṭa, which means enclosure. A wat typically contains a religious hall called a wihan, housing images of the Buddha, and dome-shaped structures called chedis or stupas that contain sacred relics or the remains of a local ruler. Some wats have a distinctive Khmer architectural feature called a prang, which is a tall, slender tower rising above the surrounding structures, serving as the central shrine of the wat.

Wats are central to Thai culture. There are over 40,000 of them in Thailand. We saw them everywhere. Their golden spires and oriental architecture make them easy to spot. Especially in rural areas, a wat can also function as a school, hospital or community center; festivals and funerals also take place here.

Our first stop in Ayutthaya was Wat Phra Si Sanphet, located on the site of the old Royal Palace. Completed in 1351, Wat Phra Si Sanphet was the royal temple, used exclusively by the royal family.

As mentioned, nearly everything here was destroyed by the Burmese in 1767, but three chedis survived. They are the grey structures with the tall pointed spires you see in this series of photos.

A handful of bell-shaped stupas also survived.

It was around 88°F and 100% humidity the day we visited; like Miami in August. Dale wisely took an umbrella for shade as we entered the park.

You can see that most of the structures were brick. Our guide explained that the brick was made from sun-dried clay dug up nearby to form a moat around the complex.

At least that’s what I think he said.

For the most part, I could only understand a fraction of what our guide told us, but I did enjoy listening to him trill his Rs and fly through his spiel. It was like having one of those foreign-museum audio guides playing in the background at fast-forward.

Here’s a good view of the three chedis all in a line:

Adjacent to Wat Phra Si Sanphet was Wihan Phra Mongkhon Bophit. Inside there’s a giant Buddha being refurbished and it looks like the place is in active religious usage, but I’m not sure and neither our guide nor the website helped much.

Our next stop was Wat Mahathat, built a little later in 1374. Here’s a model of what it once looked like:

The weight of the surviving stupas has compressed the foundational layers of decayed teak. I called this one the Leaning Tower of Wat Mahathat:

This was a very large wat in its heyday. There were groundskeepers everywhere, trimming back the vegetation.

The forest reclaims the wats if they’re not constantly tended to.

We walked around to the other side of the wall in the photo, above, to see the Sandstone Buddha being strangled by that tree. Supposedly, the Buddha’s body is still buried beneath the head.

Here were are, partially melted, in front of one of the only fully surviving Buddha statutes.

Here’s the best Buddha at this site:

Our final stop was Wat Chaiwatthanaram, built in 1630. The temple’s name translates optimistically to “Temple of Long Reign and Glorious Era.”

According to the guide book, Wat Chaiwatthanaram

is one of Ayutthaya’s most impressive temples and follows the architecture of the Khmer mountain temples of Angkor [Wat]. The tall central prang represents Mount Meru, a mountain that is considered to be the center of the universe in Hindu and Buddhist cosmology.

Here’s a model with the real thing in the background with the same orientation:

The front of the 115-foot tall central prang was being refurbished, so I waited until we rounded to the other side to photograph its details.

Off to the right of the entry was a stupa that, if I understood our guide correctly, contained the ashes of one or more of the old Ayutthaya kings or princes.

Here’s that main prang close up. Looks like one of Elon’s rockets.

Here it is again, from a distance.

And, lastly, straight on. It’s pretty much a solid structure with just a tiny room behind that door to store relics and ashes of the ancient royals. Each of the four sides has a staircase and doorway, but each entry was originally blocked by a Buddha statue, since removed.

There were, however, Buddha statue remains elsewhere throughout the wat, always headless, supposedly over 120 of them. Our guide explained that the heads had been removed by vandals and collectors. Same for the interiors of the prang and chedis.

After several hours wandering the ruins, we called it a day. On the way out of town we encountered heavy traffic.

We made one other stop enroute from Bangkok, visiting the more modern Royal Palace complex of Bang Pa-In.

The buildings that exist here now were built in the mid-1800s during the reigns of Kings Mongkut (1851–68) and Chulalongkorn (1868–1910). You’re going to hear more about King Mongkut of Siam in my next post.

whew! You two covered a lot of ground in one day!