The Kura River, also known to Georgians as the Mtkvari River, rises in eastern Turkey, flows east across Georgia and through Tbilisi, then across Azerbaijan, emptying into the Caspian Sea. The Mtkvari is to the Southern Caucasuses what the Mississippi River is to North America.

Upstream on the Mtkvari River, about 50 miles northwest of Tbilisi, is the ancient cave town of Uplistsikhe. There is archeological evidence of a settlement here more than 3,000 years ago consisting mainly of caves dug into the hillside. Its ruins now sprawl over 20 acres.

We entered Uplistsikhe from the river valley and walked up to a place used for sacrificial purposes in millennia past.

The cave city that existed here is thought to have been a major religious, political and commercial center of the eastern Georgian kingdom of Iberia from 400 BC to 400 AD. Purportedly, as many as 20,000 residents lived here, but coincident with the rise of Christianity in the mid-300s AD, people began to move away.

The city had a brief resurgence as a stronghold during the Arab invasion of the 700s AD, but was conquered by the Mongols in 1222 AD and thereafter abandoned. Earthquakes over the years since have caused a number of the ancient cave structures to collapse.

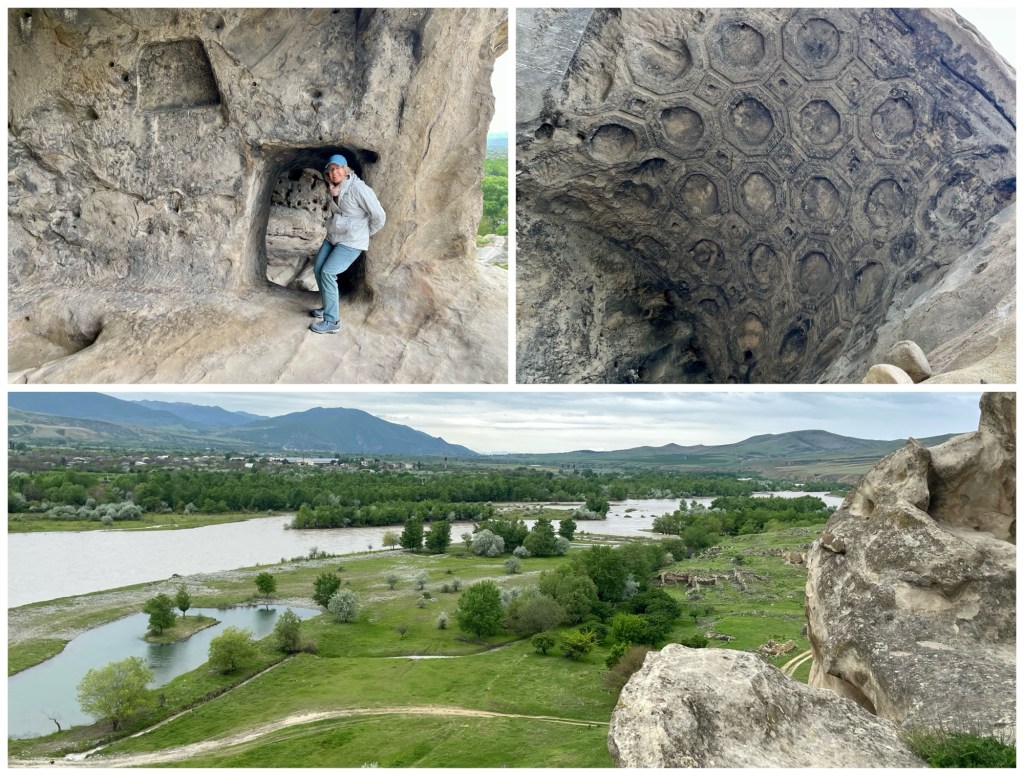

We continued our hike uphill into the city, stopping to admire this former public meeting hall…

… and the view of the Mtkvari River valley below.

Further uphill is the Uplistsuli Church, constructed of stone and brick in the 900s AD during the city’s brief restoration to prominence between the Arab and Mongol invasions. Below it is the Long Hall and to the right is the Makvliani Hall, a church and palace, cut into the rock.

We continued our walk up the main road and beyond, stopping again to admire the ruins of one of the old cave churches.

Here’s the view from the top, about 200 feet above the river:

Downstream about 25 miles from Uplistsikhe is the city of Mtskheta at the Mtkvari’s confluence with the Aragvi River. To the east of Mtskheta across the Aragvi, sitting high up on a hill, is the Holy Cross Monastery of Jvari, the site where St. Nino is said to have converted Iberian King Mirian III to Christianity in 327 AD.

In ancient times, what is now the country of Georgia was divided into two separate kingdoms: Colchis to the west on the Black Sea; and, Iberia to the east, its center being where Tbilisi is located today. Both of these kingdoms were influenced by the Persians and Hellenistic Greeks because of their location along the Silk Road.

At the time of the rise of the Roman Republic in the centuries before the birth of Jesus Christ, Colchi and Iberia were semi-independent kingdoms under Persian, and therefore, Zoroastrian, influence.

But as Rome grew into an empire in the first two centuries of the millennium, expanding east into the Caucasuses, Colchis and Iberia became client states of the Roman Empire, aligned against the Persians. And, as already mentioned, the Christian faith was adopted here as it spread throughout the Empire.

The region became a battleground between the Roman and Persian empires for the next 400 years. The Eastern Romans, then known as the Byzantine Empire, ultimately prevailed over the Persians in 582 AD. Christianity in Iberia, now under Byzantine protection, flourished. Churches and monasteries were built across the land in what became known as the Principality of Iberia (588-888 AD).

It was during this period that the church at Jvari Monastery was built. The story told is that St. Nino, with the support of King Mirian III, erected a wooden cross atop the hill where a pagan temple once stood. The cross was rumored to have mystical power, attracting pilgrims from all over to come pray before it.

In 545 AD, a small church was erected over the remains of the cross, followed by the construction of a larger cross-shaped church beginning in 590 AD, necessary due to the site’s popularity among pilgrims.

Jvari Monestary overlooks the city of Mtskheta, strategically situated at the confluence of the Mtkvari and Aragvi Rivers. Mtskheta became the capital of Iberia from around the time of King Mirian III, remaining so until the capital was moved to Tbilisi around 530 AD.

The Jvari church is in the same state today as when it was built over 1,400 years ago. Its design was copied across the realm: a cross with a longer section running east, arms running north-south, and a dome at the intersection supported by the church’s walls.

The southern entrance to the Jvari church is adorned with a bolnisi cross held by two angels. Inside are iconic paintings of St. George and St. Nino. Remnants of St. Nino’s cross are said to be entombed in the octagonal base below the dome that Dale is admiring below.

When the Arabs invaded in the 700s AD, the Iberians retreated into the mountains from which the Arabs were unable to dislodge them. Although the Arabs remained in Tbilisi for many years, they were unable to convert the region to Islam.

By 888 AD, the Arabs were gone and Iberia had been unified by the Bagrationi family who established themselves as a monarchy known as the Kingdom of the Iberians (888-1008 AD), later to become the Kingdom of Georgia (1008-1490 AD).

Leaving Jvari, we drove down to the city of Mtskheta to visit the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral there, which, together with the Jvari Monastery, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994. Svetitskhoveli Cathedral is today the second largest church in Georgia.

Construction of the original church in Mtskheta was begun by King Mirian III in 334 AD and completed in 379 AD. The current cathedral was built on top of it around 1020 AD. It is one of the most venerated Georgian Orthodox churches and is the burial site of many Georgian kings.

One of the things that makes Svetitskhoveli Cathedral so revered is that it purportedly houses a famous relic, Christ’s robe, kept under the ciborium shown in the photo below, top right.

Note the flags in the photo above. On the left is the national flag of Georgia, similar to the insignia of the Knights Templar with bolnisi crosses in the four quadrants. The other flag depicts St. Nino’s cross, the drooping arms being a result of the unique manner in which St. Nino attached the arms.

From Mtskheta, we drove north up the Aragvi River, past the Zhinvali Reservoir, to the Ananiri Fortress complex, constructed sometime in the 1200s AD as the seat of the Georgian Dukes of Aragvi.

To the left of the entrance to the church there is an inscription in old Georgian, which is not much different than the way the language is written today.

An interesting aside: Here’s an example of the typed script used in each of the countries on our itinerary. This is how you write “thank you’ in each:

- rahmat (Uzbek)

- сипос (Tajik)

- Sag boluň (Turkmen)

- təşəkkür edirəm (Azerbaijani)

- გმადლობთ (Georgian)

- Շնորհակալություն (Armenian)

Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan all use the same Latin script we use in the United States, with a few extra letters. Tajikistan still uses the Cyrillic script used in Russia, a holdover from its U.S.S.R. days.

But Georgia and Armenia? Well, that’s rather original.

And a comic aside: I was reluctant to take the photograph of the priest, above, while he was praying. But then I realized he wasn’t praying. He was checking his cellphone! Instagram? Facebook? Holy Spirit?

We continued driving north past the ski resort town of Gudauri and over the Jarvi Pass (elev. 7,857 feet) to the village of Stepantsminda where we changed vehicles in order to drive up to the Gergeti Trinity Church (in Georgian: გერგეტის სამების ეკლესია), built in the 1300s AD.

Due to its remote location, relics from other Georgian Orthodox churches were brought here for safe-keeping during times of invasion. You enter through the building on the right, sort of a guard tower.

Here’s Dale about to go in.

The interior of the Gergeti church is lit solely by candles and a few slit windows and openings in the dome. The church is still in use, as evidenced by the villagers we passed on the way up, making the 1.5 hour trek from the village to worship.

There was a beautiful view of the surrounding mountains as we exited through the guard tower.

And down below? That’s Stepantsminda.

From here it’s just over 5 miles to the Russian border, north of us.

Incredible. That is all that I can say.